Friday, December 30, 2005

Saturday, December 24, 2005

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

THE SWEET SMELL OF SERENDIPITY

I'll come back to the vendetta thing next post. There's not a lot more. But in the meantime...

I've been reading Andrew Lownie's The Edinburgh Literary Companion, which is chock-full of useful quotes and selections, and on pages 19-20 has a section on the Luckenbooths:

'Matthew Bramble in The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker thought the High Street:

would undoubtedly be one of the noblest streets in Europe, if an ugly mass of mean buildings, called the Lucken-Booths, had not thrust itself, by what accident I know not, into the middle of the way...

This view was shared by Scott in his famous description of the Luckenbooths in The Heart of Midlothian:

For some inconceivable reason, our ancestors had jammed into the middle of the principal street of the town, leaving for passage a narrow street on the north, and on the south, into which the prison opens, a narrow crooked lane [...]'

Both Allan Ramsay and William Creech, booksellers and publishers, had their premises in the Luckenbooths, and Ramsay opened the first public lending library in Britain there in 1725.

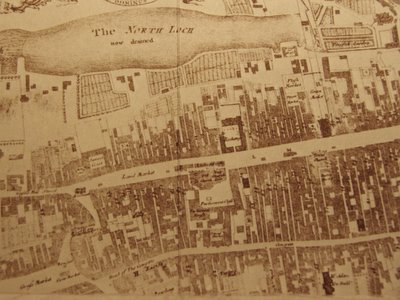

But it was difficult to visualise, given the pleasant, airy width of the High Street today next to St Giles Cathedral, with its view down to the Forth, until totally by chance I came across a fold-out map of Edinburgh of 1765 in my Nanna's copy of, erm, Ranger's Impartial List of the Ladies of Pleasure in Edinburgh (1775). (I hasten to add this is a 1978 reprint by Paul Harris Publishing, and not an original edition.)

One can see Old Church (St Giles, presumably), Parliament Square, Parliament House, and the Exchange (now Edinburgh City Council Chambers). B is the Tolbooth prison, C is Hadden's Hold[?] Church, and D the Tolbooth Church, and the strip to the right of B, one can just read, is marked Luckenbooth.

(Thanks to the United Nations Command for Law Enforcement for the title of this post.)

FATAL RESONANCE

From Iain Finlayson’s The Scots (

The Highlanders want less, generally, while the Lowlanders want considerably more. Moray McLaren in The Scots, published in 1951, analyses the Highlanders’ character with some subtlety, claiming that they march to a different tempo to the rest of the British, that their apparent idleness is in fact due to a different [and, I’d argue, more humane] concept of time. [See also “Repent, Harlequin!” said the Ticktockman] […] People of the mountains and those who live by the ocean are peculiarly prone to this sort of faith in the slow, undying movements of nature that heal all things and reshape them according to ineffable laws that tend towards the balance of all things. Their apparent apathy, therefore, can be explained and excused by the Highlanders’ sense of fatalism. As McLaren puts it: ‘his greatest temptation when faced by crude, cruel material, men and circumstances, over which his bravery cannot, or does not seem likely to, prevail, is to withdraw too easily into an inner world of his own thoughts, inactive, dignified, and doomed.’ [p. 39]

Compare this to Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands (Penguin):

As I listened I thought once again how precarious was the existence of the Bedu. Their way of life naturally made them fatalists; so much was beyond their control. It was impossible for them to provide for a morrow when everything depended on a chance fall of rain or when raiders, sickness or any one of a hundred chance happenings might at any time leave them destitute, or end their lives. They did what they could, and no people were more self-reliant, but if things went wrong they accepted their fate without bitterness, and with dignity as the will of God. [pp 226-7]

I might also add an anecdote from Thomson’s Nairn in Darkness and Light about a family who had been flooded out of their black house; this was the third time that this had happened to one of them, an old man in his seventies, but somehow he remained resigned and even cheerful. At least, I’d add it if I could find it.

The key factor here, of course, is poverty. If you don’t have the resources to change things, you accept them. But it has an interesting corollary, which is the vendetta. Thesiger again:

Vindictive as this age-old law of a life for a life and a tooth for a tooth might be, I realised none the less that it alone prevented wholesale murder among a people who were subject to no outside authority, and who had little regard for human life; for no man lightly involves his whole family or tribe in a blood feud. [p. 107]

This comment follows a story about one of Thesiger’s companions, who had come across a fourteen year-old boy from the

His had been a human, intellectual curiosity that could not, and should not, be confused with the interest of those whom society and State paid to capture and consign to the vengeance of the law persons who transgress or break it. At play in this obscure pride were the centuries of contempt that an oppressed people, an eternally vanquished people, had heaped on the law and all those who were its instruments; a conviction, still unquenched, that held that the highest right and truest justice, if one really cares about it, if one is not prepared to entrust its execution to fate or God, can come only from the barrels of a gun. [To Each His Own, Leonardo Sciascia, NYRB 2000, p. 120]

This comment about not being prepared to rely on fate or God is curious, because the law of the vendetta was seen, historically, as so overwhelming that there was no alternative. It might as well carry the weight of God and fate working in cahoots:

D’Agostino always expected to be asked whether he would commit his crime [five vendetta murders] again cold the clock be put back, and his reply was always the same: ‘Surely you don’t imagine I had any choice, one way or the other? Honour’s honour and a vendetta’s a vendetta. You might say that destiny put its big fat thumb in my neck and squashed me like a beetle.’ The warders nodded their sympathy and their agreement. That was the way it was. [The Honoured Society, Norman Lewis, Eland 1984, p. 27]

It should be added that D’Agostino was treated with immense respect, the only prisoner, not excluding a general, in the whole of

Thesiger’s belief that the blood-feud acted as a stabilising force, preventing wholesale massacre out of fear, doesn’t appear to hold up, at least not in the Sicilian context:

By 1960, nearly one-tenth of the population of Godrano had become casualties as the feud developed and spread, the latest victim - in the absence of eligible adults - being a boy of twelve. [The Honoured Society, p. 24]

Moreover, this form of justice, if one can call it that, is not only nearly unstoppable, it is indiscriminate:

In

While in

As a rule Bedu do not nurse a grievance, but if they think that their personal honour has been slighted they immediately become vindictive, bent on vengeance. Strike a Bedu and he will kill you either then or later. It is easy for strangers to give offence without meaning to do so. I once put my hand on the back of bin Kabina’s neck and he turned on me and asked furiously if I took him for a slave. I had no idea that I had done anything wrong. [Arabian Sands, p. 163]

All of the above throws an interesting sidelight on clan warfare and feuding in the

Monday, December 05, 2005

WHY INCOGNITO IS MAGNIFICO

There's a basic assumption in the UK that the onus falls on the authorities to prove that you're not who you say you are, rather than that it falls on you to prove that you are who you say you are - or as a cartoon in a 1993 issue of the New Statesman put it (when PM Major and then Home Secretary Michael Howard were proposing ID cards), "Because everyone is guilty until proved innocent".

Historically, this belief, principle, call it what you will, of popular resistance to state control has some interesting manifestations. As I recall, one of the complaints against Charles I was that he wanted to establish a standing army - this was resisted on the grounds that it could be used by the monarch against Parliament.

A similar principle was applied against the proposal to establish a metropolitan police force in the early 18th century, despite the violence, lawlessness and difficulty of obtaining justice that plagued the capital. A state-established, state-controlled police force smacked of French absolutism - something that English liberty stood four-square against.

In a broader sense this raises questions about the role of the state in public life.

Of course, this cuts both ways. In the

As a final example, when I was working in